In 2005, when an importer asked their best manufacturer for a report that shows their own inspection findings, they seldom received a document. They were usually told “no problems were found”. Getting a few digital photos by email was already an accomplishment.

Things have changed. In most industries, the best manufacturers are used to producing QC inspection reports for their internal use. There are several reasons for this:

- It is a management tool — quality keeps production honest, and shipping a substandard batch requires multiple sign-offs.

- The factory top managers have understood that savings a few bucks today and getting heavy chargebacks (or even losing a significant customer) in 2 months is not good business.

- They sometimes decide to share their own reports with customers, as an attempt to avoid being inspected (since welcoming an inspector, unpacking, repacking, etc. takes a lot of time). And sometimes it works.

As a rational purchaser, I would certainly want to look at the opportunity to reduce, and maybe even eliminate, the QC inspections performed in the best factories that ship products for me.

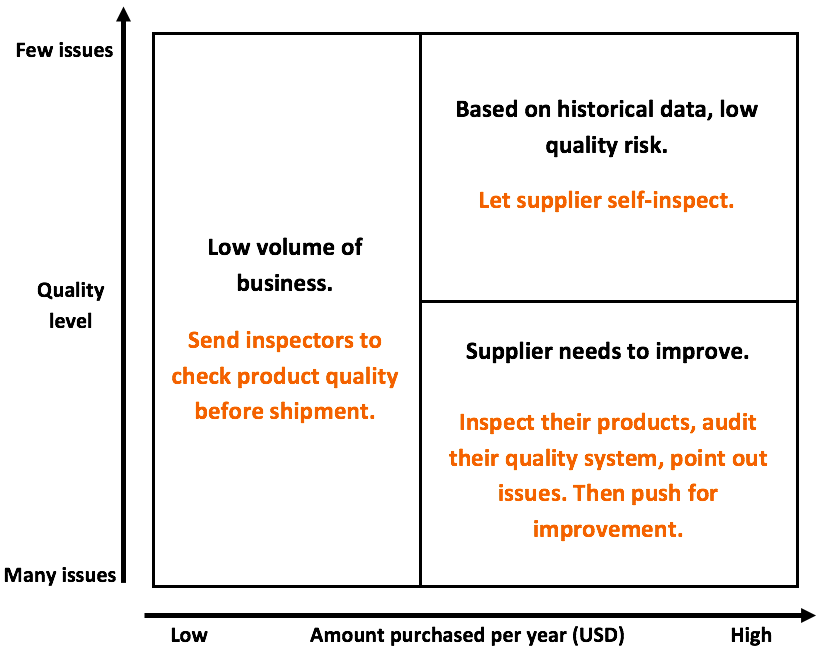

From my discussions with a number of quality and procurement managers in China, more and more of them are coming to look at their supplier base this way:

Category 1: low volume of business

These suppliers only ship products irregularly. The amount is low. Purchasers don’t even know if the same manufacturing facility is used over time. It doesn’t make much sense to get to know them better. No change for these ones!

Category 2: low quality risk based on historical data

These suppliers have demonstrated that (1) they are not likely to play games, and (2) their product quality is consistently good. As a reward, they can be extended a higher level of trust. These are the best candidates for supplier self-inspection.

(Let’s face it, random inspections don’t catch all issues. I wrote before about the 5 main limits of AQL inspections. It is an imperfect tool.)

This can be done in combination with a skip-lot inspection program (the buyer can decide to check 20% of the batches before shipment randomly and with minimal prior notice, for example).

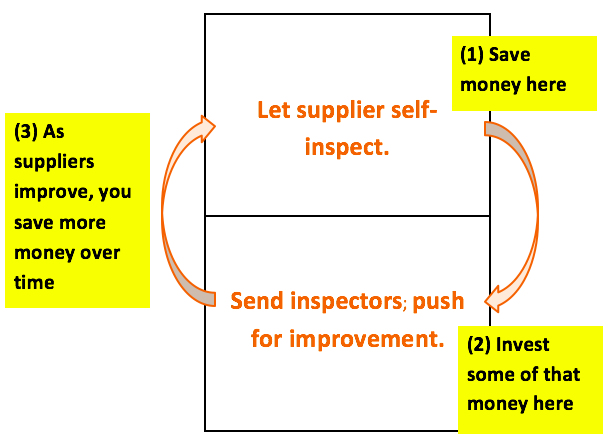

Unfortunately, this category of suppliers might represent 10-30% of the total purchased amount. What about the other suppliers who also represent a substantial flow of business and that are not really good?

Category 3: suppliers that need to improve

You still need to pay for the inspections of their products, and pay for their quality issues (whether you detect them or not, they create delays, arguments, etc.).

But hopefully you want them to get better over time. If they show positive signs (the boss is motivated to make changes etc.), it might make sense to help them.

What you can do as the buyer

Try to set up an overall supplier development program. You could look at the categories 2 and 3 this way:

How can you push some suppliers for improvement? Here are a few basics…

You need regular monitoring and data collection:

- Audits of the factory’s quality system and processes

- Most common defects per process/product type

Based on these data, corrective action plans can be set in motion and their effectiveness can be followed up. If they do this seriously, and if they get help where necessary, they can probably be awarded the privilege of self-inspections.

Now, letting a supplier check their own product quality should only take place under certain conditions. And there will always be limits to that approach. I’ll write a follow-up article on that…

No comments:

Post a Comment